Unit 1. Approaching women’s issues

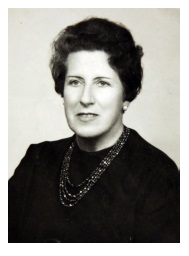

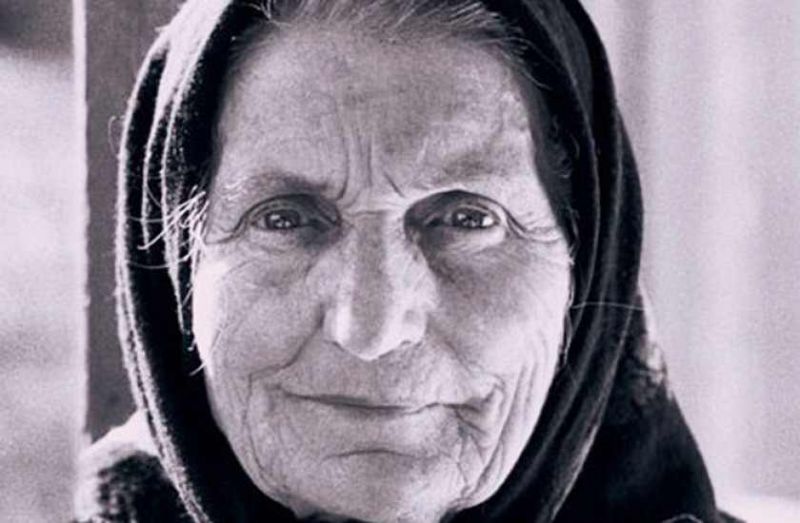

With these stories, I wanted to open the discourse that makes the reader face taboos related to ageing; to open up the topics such as weakness, sickness, fear of dying, loss of dignity. This book talks about being lost and insecure in everyday life situations that used to be routine situations. I developed this book slowly, with consciousness about my own ageing, especially after my parents died when I began to listen to voices around me, voices of older people I hadn’t heard before. Everything is written in stories, from the irreversibility of the process of becoming invisible, guilt regarding parents, and even stories that aren’t mine, but that have impressed me profoundly.

Slavenka Drakulič, The invisible woman and other stories

Some might argue that not only literature but also the field of adult education have been dealing with gender issues for a long time. Women's participation, or lack thereof, in adult education has been explored for decades. Preferences in women's learning styles have been examined. Different social roles have been in focus from the role of mother and spouse, to their professional roles. Their responsibilities have been in focus as well as the consequences the changes in women's roles have had on women's identities. But women's identities have rarely been examined as such, as being theirs, just theirs and not in relation to men and to their reactions in the same contexts, though, as we have seen before, older women should know who they are and should be aware that they can grow and can become who they feel they can become. Nevertheless, studies about older women and the gender capital they bring into adult education have seldom been explored and taken into account while developing an educational programme. In addition, older women do not overtly require more visibility. They adapt themselves Figuring out how women can overcome this state, struggle for gender equality, and become aware of who they are is a basic task in developing educational programmes for older women.

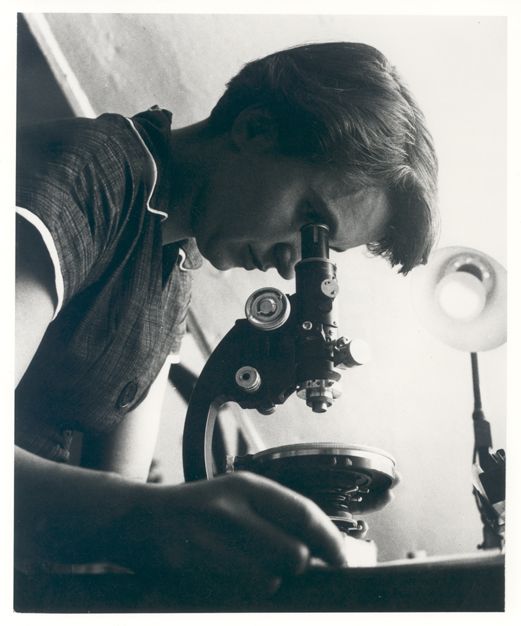

Focusing on women's situations, you will discover that they are described in relation to men's situations. And you will also discover that women are missing from the data. We can deduce that analyses, theories, research studies or practices are only about half of the population. To illustrate this point, Frederick Gros, a French philosopher, author of the best-selling book Philosophy of walking argues that walking leads to thinking and that many great thinkers in history described their walking as a thinking process (Gros, 2000). He does not mention a single woman, and the reader rightly asks her/himself why there are no women mentioned on the list of great thinkers. The struggle for equity between women and men would bear more fruit if there were data concerning both.

Adult educators repeat that groups of older people are heterogeneous due to their disparate life experiences and reference frameworks. They forget, however, to stress that the heterogeneity of older people is also due to their gender. If data regarding older people, in general, are not important for statistical studies, data of older women seem to be even less so. In the PIAC study, for instance, people over 65 were not addressed by member States, except Germany, which produced an additional study addressing people over the age of 65 and their needs.

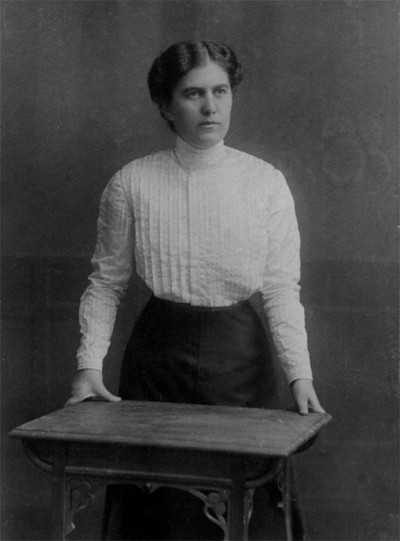

There are numerous approaches of women’s issues in research and education. The most common one is the oppositional approach, based on biological sex distinctions between men and women. Differences between men and women are often presented as a dichotomy—women opposing men and vice versa. Women are frail and powerless; Men are strong. Gender typing starts early with sentiments that boys should not show emotions, and that girls should behave properly.

This oppositional approach has been intensified by different religions that have analysed and separated the role of women and men. Women and men have had different economic roles in the field of production, reproduction and consumption. Women are subjected to men politically, economically, pedagogically, and in virtually all ways in which society reflects its power, power that is, with few or no exceptions, invested in men. In The Metaphysics of Morals, Kant writes, to "the natural superiority of the husband to the wife in his capacity to promote the common interest of the household," and mentions the lack of all women's fitness to vote. (Mosser, Kant and Feminism by Kurt Mosser, Dayton/Ohio)

Since men and women are not the same, they are defined by many masculine and feminine attributes that need to be acknowledged in older adult education. Women and men should be treated equally. But is it really so? Gender differences are constructed and deconstructed. Men and women’s identities are formed differently. Gender is not stable.

On the contrary, it is rather dynamic, depending on time and space, and the social, political and historic cultural contexts within. Researchers like Hugo, 1990, Lewis, 1988, Stalker, 2005 refer to Belenky et al. (1986) arguing that women are unique but absent from research studies, and attention should be devoted to them. Other research argues that women and men are both complex and diverse categories. Dichotomous approach functions differently in different contexts. In patriarchal contexts, there is a definition of men’s values, abilities and actions and women’s values, abilities and actions as deficient, relative to men. As a result, stories, experiences and knowledge of all women are needed in order to achieve their genuine empowerment.

1900 – 1978

1900 – 1978

1900 – 1978

1900 – 1978

1900 – 1978

1900 – 1978